The Federal Reserve has to be pleased with the way their tightening cycle has gone, not that they ever wanted to be here. The Fed has engineered meaningful tightening, markets have had nasty reactions in the downward direction, and yet we haven’t had a true financial panic. Further, job opportunities are still relatively plentiful, and yet we’re already seeing high-skilled labor negotiating power is shrinking in some sectors, suggesting labor cost pressure on inflation is waning or at least peaking, even though labor demand is still strong. Further, inflation has dipped a bit in the last month, but it is still very high–significantly above the Fed’s longer term goal of 2% inflation, and is pervasive throughout the economy (i.e., it’s not just in energy costs). We’ve had two straight quarters of slightly negative growth, but the underlying momentum of the economy still seems at least o.k.

Prior to Mr. Powell’s remarks Friday at Jackson Hole, markets had strongly recovered from bear market territory, and longer term treasury interest rates have fallen, suggesting markets are pricing in rate cuts–not further increases–sometime in the not too distant future. Mr. Powell’s speech on Friday was pointed, making clear that the Federal Reserve intends to rise up at this Volcker moment*.

Here are a few of the key tidbits from his speech.

“Without price stability, the economy does not work for anyone. In particular, without price stability, we will not achieve a sustained period of strong labor market conditions that benefit all. The burdens of high inflation fall heaviest on those who are least able to bear them.”

“While higher interest rates, slower growth, and softer labor market conditions will bring down inflation, they will also bring some pain to households and businesses. These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.”

“Restoring price stability will likely require maintaining a restrictive policy stance for some time. The historical record cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy.”

“That brings me to the third lesson, which is that we must keep at it until the job is done. History shows that the employment costs of bringing down inflation are likely to increase with delay, as high inflation becomes more entrenched in wage and price setting. The successful Volcker disinflation in the early 1980s followed multiple failed attempts to lower inflation over the previous 15 years. A lengthy period of very restrictive monetary policy was ultimately needed to stem the high inflation and start the process of getting inflation down to the low and stable levels that were the norm until the spring of last year. Our aim is to avoid that outcome by acting with resolve now.”

This was a great speech from the Chairman. Given the circumstances that they have had a large part in creating, I couldn’t have asked for a better speech. Yet markets didn’t like it, as they were hoping for a nearer term monetary easing, with the major stock market indices in the U.S. losing 3-4% on Friday. It’s not too surprising; markets have become accustomed to quick returns to easy money policies at the first sign of trouble over the last few decades, with the Fed “put”** an openly acknowledged reality. But talk is cheap, what are they actually doing? Despite the murkiness of how they should respond (see my post from yesterday), I think they’re doing rather well in their attempts to slow inflation down without throwing us into an ugly recession. Here is what the Fed is directly doing:

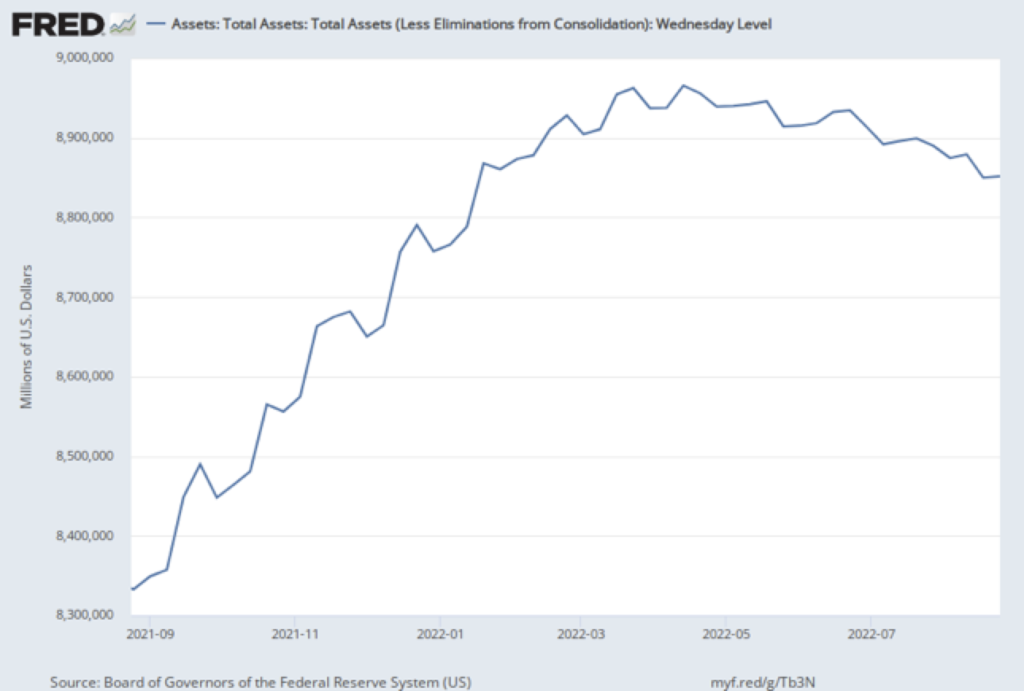

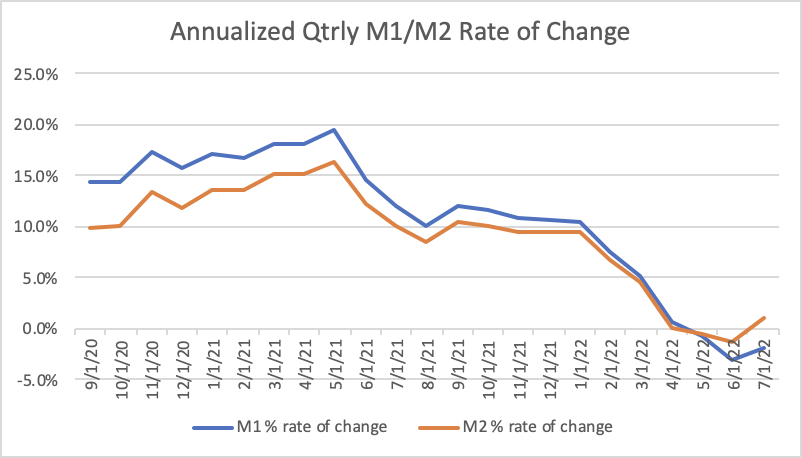

The Fed continues to slowly drain some of the $5T it put into the economy, although the last month was slightly up. But quantitative tightening is still coming, with acceleration this fall. But how is this relating to the actual money that gets into the economy?*** I’ve updated my chart on the quarterly annualized monetary aggregates growth rate in the following chart:

As you can see, the economy actually started having some growth in the broader M2 money supply in the last month. In an ideal Milton Friedman world, we’d have something like a 3% growth rate in the money supply: that would allow the economy to grow at 3% (long term historical trend, although we’ve not done that for a while) and inflation would be around zero. Having M2 negative over the last few months (and decelerating since the first of the year) is one of the main reasons why we’ve had two straight quarters of negative GDP growth. But if you’re not rooting for recession, and I’m certainly not, you’d like to see low and stable money growth–something like a Friedman rule. So getting us back to that low and stable money growth is where we want to go, and the Fed seems to be taking us there. Markets may not like it, but I think they’re doing pretty well now in their attempt to engineer a soft landing. I don’t think we’ll have the true soft landing (we’ve already had two quarters of negative GDP growth), but I think we can be hoping for a “softer” landing. If Mr. Powell keeps his word, we may be able to stop the inflation they’ve created without massive pain to main street. I certainly hope so.

* Paul Volcker was the Chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987, and his tough policies broke the back of inflation, but with much economic pain.

** The Fed “put” is the idea that the markets have protection in the downward direction as the Federal Reserve won’t allow them to drop “too” far–effectively giving market participants a put option, which is often used to protect investors by giving them the right to sell at a defined price. Except the Fed gave this option, investors weren’t required to pay for it. You and I paid for it with the imbalances and ultimate inflation it created.

*** The Federal Reserve controls the base of the money supply through its asset purchases, but the financial system (banks) and individual decisions to take out loans decide how much money enters the economy. See my youtube video if you’d like to know more.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach