This is a claim I make to our principles students in the first part of our economics class, as I reflect on the economic way of thinking, a discussion topic fairly standard in more textbooks. Essentially, the economic way of thinking forces one to fully consider all costs and all benefits of any choice. In our public discourse, we often hear one side or the other accentuate the positives of any particular policy so much that they refuse to see the other side–the costs. But looking at all costs, and all benefits forces you to consider what the other person says. You will still likely have disagreements with others, but you can usually then see the differences as reflecting just the subjective values that each one of us has. Even for Christians, we have an objective value system (God’s word in the Bible), but that objective value system is subjectively assessed by our individual filters (and those often reflect not only our capacity as image bearers but also that we are fallen). So we shouldn’t be surprised that we have differences.

As a particular way of describing it, Henry Hazlitt as usual has it about right, where he says we have a

“persistent tendency of men to see only the immediate effects of a given policy, or its effects only on a special group, and to neglect to inquire what the long-run effects of that policy will be not only on that special group but on all groups. It is the fallacy of overlooking secondary consequences.

In this lies almost the whole difference between good economics and bad. The bad economist sees only what immediately strikes the eye; the good economist looks beyond. The bad economist sees only the direct consequences of a proposed course; the good economist looks also at the longer and indirect consequences. The bad economists sees only what the effect of a given policy has been or will be on one particular group; the good economist inquires also what the effect of the policy will be on all groups.”

Hazlitt will subsequently summarize the long quote above like this:

The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.

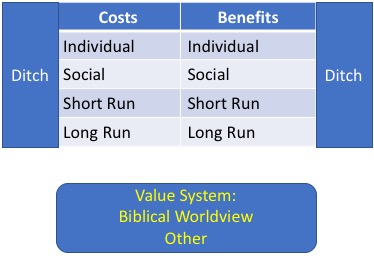

The diagram below somewhat captures what I have in mind. You can see that a full assessment of costs and benefits includes both individual & social, and short run and long run considerations. This analytic decision will always have a foundation of our individual value systems. But if we share the same values, and fully consider all costs and benefits, we’re going to come to very similar policy prescriptions. It is almost always the case that any significant disagreement on public policy is either a differing value system or a failure to fully consider all costs and benefits. This is why I don’t really need to tell people what to think–if I want them to come to the same conclusions as I do, it is sufficient to train them how to think. Then we’ll generally be pretty close. This doesn’t mean we don’t address some aspects of what to think. Foundational economic scarcity, opportunity cost, law of demand, etc. are basic building blocks we have to start from. And of course I want to shape their Christian world view, with foundations of Genesis 1-3 and a Christian anthropology of humans being both in the image of God and yet fallen the most critical biblical building blocks for economic theory. From these very basic foundational concepts, the rest is mainly how to synthesize.

You should also notice the ditches in the above diagram. They are a danger to each of us, and they are also where someone you are in a conversation with in this partisan age will try to place you. As an illustration of this, you don’t need to look very far in my posts to find a frequent critic say in response to my belief that the Obama era growth in regulatory activity was bad and Mr. Trump’s deregulatory agenda is positive to immediately try to push my belief into the ditch: “Contrary to what you believe, by faith, not all regulations are bad.”* So beware; don’t go into the ditch yourself, and be aware that many of your political opponents will falsely try to claim that you are in a ditch.

Of course given the necessary brevity of a blogpost, its understandable that a reader might think there are costs/benefits of any issue under discussion I’m missing. That’s where good commenters come to play–and my challenge to each of you–ask good ??s, try to show the logical implications of where my comments (or others) might go. Let’s have a good discussion and debate. We can do this, and we can do it better than the culture at large. Let’s each of us sharpen how we think, and be less concerned with what the other person thinks.

* I don’t think all regulations are necessarily bad. However, I am suspicious of many regulations (especially the growth in regulations) not only because of the cost (which tends to hurt those most disadvantaged disproportionately) but also because of public choice considerations. A fuller explanation can be found here.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach