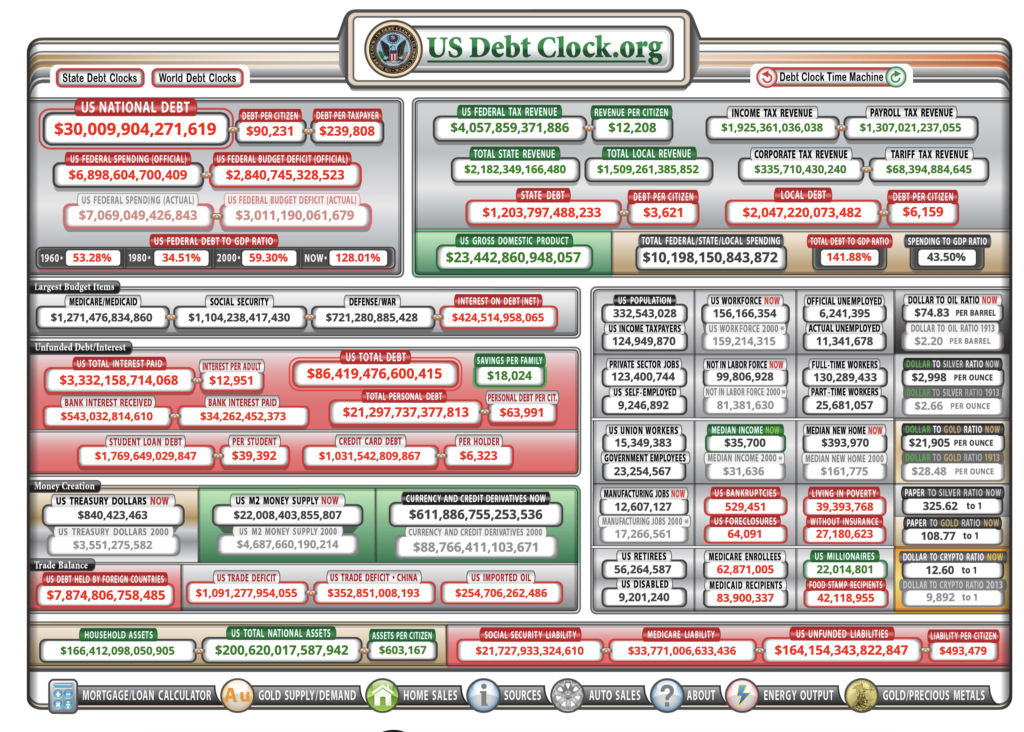

Our national debt has now crested $30T, with a gigantic yawn from the Biden Administration, the national media, and yes, most economists. The debt doesn’t matter, you see “we owe it to ourselves.” And besides interest rates are low, markets are begging the government the government to spend (as former Federal Reserve Vice-Chair Alan Blinder has argued*). The problem with debt is that debt isn’t a problem–until it’s a problem. And once it’s a problem, there is no easy putting humpty-dumpty back together again. The value of a currency, like any other value, is to some degree speculation about the future. And with money specifically, its value is all about trust. I’ve long argued, following Jim Grant, that the U.S. dollar remains strong because we’re the world’s cleanest dirty shirt. What, after all, is the alternative to the dollar? The Russian Ruble? The Euro? The Renminbi? No, for better or worse, and it certainly is worse, there really is no alternative to the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. But one day that trust will crack. And when trust slips away, it will be like trying to grasp the wind to get it back.

There are many in the “high debt isn’t a problem, let’s just keep spending” crowd who will point to Japan and other highly indebted countries as arguments that the U.S. is not in any trouble. The first and obvious point is, who wants an economy like Japan’s?** But they are also a different economy, with a saving rate a good bit better than the U.S.’s., leaving more money for the government to spend, among other things. Reinhart and Rogoff’s book is still worth a read, as their voluminous history shows that once nation’s get to a certain point in debt, bad things happen.*** Yet whatever that certain point is, we know that historically, countries with high debt levels either default (if they owe the debt in an external currency) or debauch (inflation, if they owe the debt in their own currency).

In most cases the tipping point is going to be related to the costs of servicing the debt, but as we’ve noted here at BATG, the Fed has for over a decade kept servicing costs very low by monetizing the debt with low interest rates. Indeed, my argument is that the Fed is the prime enabler of this political malpractice. Yet Milton Friedman will have his day: inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. The Fed for months tried to say that the inflation levels were nowhere a monetary phenomenon (after printing $5T of new money!!!!!!!!!!), but they’re finally having to cry uncle, and are proposing to raise rates this spring, and they are dialing down their current “emergency” stimulus (scheduled to end in March).

Long time Berean readers know I’ve suggested this fiscal and monetary profligacy will end badly, and this excellent summary article over at National Review shows us some potential reasons why.

But lest you think this is just a future meltdown possibility, make no mistake, the $5T of debt monetization that the Fed just did has already raised your taxes significantly (via the inflation tax) and is making real interest rates further negative, punishing those foolish people who decide to save. There is no free lunch, and the bill will be paid–Adam Smith will have his day.

* Trust me, it’s in here somewhere in one of his voluminous WSJ op-eds (alas, google no es mi amigo). As memory serves, Blinder argued that the low interest rates meant that markets/private sector were practically begging the government to spend on public goods since the cost was so low. EDIT Update: This one is close to my memory, but I’m still thinking there is another one pushing this.

** Japan has been stagnant (slow & low growth) for thirty years. Not the model I’d hope for us.

*** What that rate is, is debatable. R&R’s book showed that when a nation had a debt greater than 90% of GDP, the economy generally grew at a slower rate. However, that conclusion was found to be due to a spreadsheet error, and there is really limited data at the extremes with very unique circumstances in each of the countries, so it’s hard to put a “this is the tipping point” # with any confidence.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach