I avoid cable television news as much as possible. On this day, I just had to watch. The smoke billowed across the skyline, pouring out of Notre Dame, the most famous cathedral in the world. The roof collapsed and then the spire. The embers glowed into the night. Stunned Parisians responded by singing hymns.

I have been to Paris twice in my life, both times with student groups. As part of a World War II tour, Paris is something of a respite. Though it was occupied, and the sight of its own set of sorrows, the City of Lights did not suffer under a blitz, and it wasn’t firebombed. Paris stands mostly untouched from the ravages of the Twentieth Century. Fittingly, the Eiffel Tower dominates the skyline, a symbol of the modern age’s triumphant optimism. Though Paris survived the great wars, many of her sons did not. They fell at the Marne or in Verdun in World War 1, and bore the brunt of the Blitzkrieg early in World War 2. Two generations of Frenchmen and only some of them came home.

Notre Dame is from a different age. Nestled against the Seine, the cathedral dominates its own slice of the city. It is more than a landmark, of course. Notre Dame reminds us of a past that never existed in the United States. Like most cathedrals from the era, it is built in the shape of a cross. It is a physical representation of the crucified Christ, a living monument to the hope God gave us through his Son. At the same time, Notre Dame pulls the eye upward. The two towers monopolize one end of the building, and the flying buttresses surround the structure, pointing both inward and to the sky.

I have grown up in a theological tradition that discounts space for worship. The church is not a building; the people are the Body of Christ. We worship in gyms, strip malls, converted warehouses, and, in the extreme, sometimes literally underground. We don’t need a building to relate to God or to enter into his presence. Protestants, especially of the low church variety, are iconoclastic by nature, and that mentality spread into our approach to physical space. Theologically, I think this is correct.

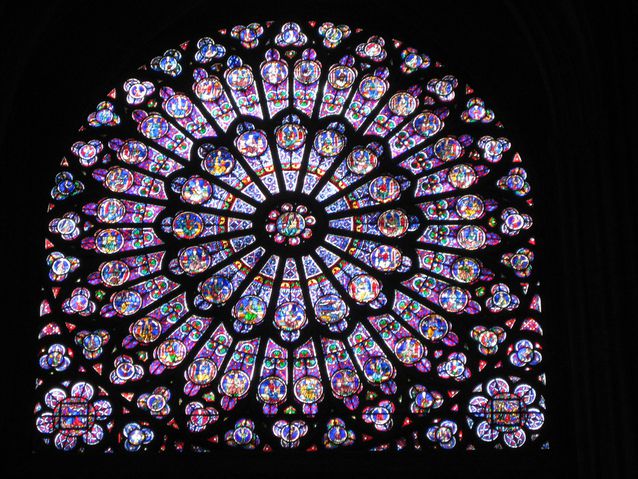

But walking into the corridors of Notre Dame provides a powerful counterargument. The beauty and majesty of this sacred space is awesome. Sounds reverberate. The stained glass windows tell the story of Scripture. The rose window, seen above, is a testament to the beauty of the divine. It is the product of an ancient craft, the outworking of skills and talents that remind us of God’s own creativity.

We don’t need a cathedral to worship God. Human structures don’t guarantee fidelity to His truth. By disconnecting our worship from beauty, and by failing to cast our gaze upward, and away from ourselves, we still miss something. Perhaps this is the hole we are filling when we stare at animated slides, or when we pull emotion from a worship team, or gyrate–just a little–as the bass thumps. Entering into God’s presence is a whole body experience and sacred spaces can transport the self and the mind in a unique way.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach