“What the nomads are doing is not that different than what the pioneers did. I think Fern’s part of an American tradition. I think it’s great.”

Fern lives in her van, which has broken down and she is unable to fix it. She arrives, via bus, at Dolly’s house. Her sister lives on a clean, suburban lane. A picnic is happening and Fern’s discomfort fills the screen. The food is ample. Used to the infinite solitude of the open sky, Fern mires in small talk. The conversation turns toward real estate, which Dolly’s husband, George, sells. The canyon between Fern and the remnants of her family is as big as the desert she favors, and as cold as the winter nights she spends wrapped in layers, hoping to survive.

To defend her sister, and explain her to friends, Dolly compares Fern’s lifestyle to the pioneers, who lived long stretches in their wagons. They also stared at an unending horizon, and surely worried the cold would come so deep they may slumber forever. Like Fern, the pioneers were searchers. Dissatisfied with their old lives, or curious enough to find new ones, they left what was known–friends, family, and familiarity. Fern has done the same, Dolly says. Dolly, we find out, is a good sister, and so is Fern, but their goodness is as different as their lives.

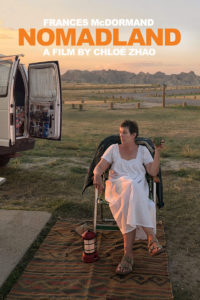

Fern (played by Frances McDormand) is leaving a town, Empire, we are told in the preamble, that lost its zip code when a local plant went under during the 2008 recession. She lives in a white cargo van she has equipped with a bed, a gas burner for food, and a five gallon bucket as a toilet. Her year is defined by the seasonal employment that comes along. Amazon needs holiday help, and they pay for campsites. Fern waits tables, cleans a campground, and shovels beets. She never starves, at least not for food. Fern works hard. There is nothing lazy or shifty about her.

On her travels, she encounters other nomads. They have an annual gathering where they swap goods and stories. They do laundry and puzzles while they wait. They are friends that sometimes border on family. They are bound, it is clear, by deep needs they can’t quite fulfill in one another.

Nomadland,* directed by Chloé Zhao, is ponderous in every dimension of the word. The film takes it time, like a master sculptor who agonizes over every strike of the hammer. As the shards fall away, revealing the shape beneath, patience is rewarded, but what remains is not polished marble with smooth curves. This sculpture is all jagged edges that cast shadows that conceal as much as they reveal.

As a film, Nomadland** is a marriage between Michael Moore and Terrence Malick. There are only two professional actors in the cast (from what I can tell). McDormand and David Strathairn (he plays Dave) shine, but not much more than the amateurs. I am sure actors could have played Swankie or Linda May, two of Fern’s occasional companions, but these real people feel like they carry real struggles. Nomadland benefits from this choice.

The politics of Nomadland bear some consideration. This is, make no mistake, a critique of the American economic system. The film doesn’t preach, and the message doesn’t detract from the artistic achievement. It is organically political. There are no obvious villains, not even Amazon, which is shown to be clean, decent, and modern enough to be just barely heartless. The antagonist is the system that begets nomads. The cracks in capitalism are so large, the film suggests, that white vans, filled with people, slip right through them.

Still, Fern makes her own choices. Fern has opportunities to live differently and she rejects them. She has family. She has friends. They reach out to her, lovingly and mostly without judgment. She chooses her own life, even to the point of desperation. Fern finds joy alone, which is the great beauty and tragedy of Nomadland.

In yesterday’s westerns, the scenery was the uncredited star. The majesty of the plains, the otherworldly rock formations of Utah and Arizona, and the shimmering desert filled the screen, obscuring even the most famous actors. Nomadland is filmed in similar locations, but instead of horses, there are vans. Instead of tumbleweeds there are lawn chairs. Instead of square jaws wearing white hats, there is white hair perched atop lined foreheads. This is a new kind of western, the film implies, for a new kind of America.

Nomadland sees a diseased system that is unstable and dangerous, especially for those on the margins. Americans are uprooted and disconnected from their families, floundering without communities. They are ill-equipped to handle grief and disappointment. Instead of finding meaning in our things–houses, cars, and clothes–we should search the universe for our place within it. Nature is its own kind of balm. A stream. A wave. A sky. A star. These bring beauty to life, but you have to find them. Along the journey, if you are lucky, you will run into a Swankie or a Linda May.

There is much longing in Nomadland, and it comes close to wisdom. We are nomads not because our material needs are unmet, or even because our families are fractured. We are nomads because our spirits are shriveled and unfed. We are disconnected from all things because always within us there are divinely shaped holes in our hearts. Nature sings because of the one who directs the choir. It is not just me, staring into the expanse, feeling small and alone. It is me, seeing the majesty of God, trembling to think the one who painted the stars cares even for me. Within God the wandering soul finds rest. No van required.

*Nomadland is rated R because of one scene where Fern bathes nude in an open stream. The camera does not shy away from her, but it also contextualizes her. There is nothing lurid or sexualized in the placid moment.

**Nomadland earned Academy Awards for best picture, director, and actress. While the competition was weak, and I cannot claim to have seen all the other nominees, the film’s wins are deserved when compared to past winners.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach