As the U.S. policy makers continue to demand head toward negative interest rates (thank you Mr. Trump, NOT!), I thought it would be helpful for a short review. So, here are some common questions and my answers.

What are negative interest rates? A negative interest rate is simply the result of someone paying higher for an asset than they will receive in the sale (to include the discounted cash flows of any interest they receive during the course of the holding period). So if you pay $10,000 for a zero coupon bond that would pay you $9800 one year later, you would have received a negative interest rate of 2%.

How do interest rates go negative? At its simplest level, buyers of assets (bonds, T-bills, etc) have such a high demand for those assets that they bid up the price until they are actually losing money by doing so. Of course this seems absurd, and has been for all of monetary history (with one exception that I’m aware of) until recently, so let’s dig deeper.

Why would anyone be willing to take negative interest rates? Some market participants need to have highly liquid assets that can quickly be converted into cash for trade settlements. Consider a hedge fund that sells one asset for $25M and is going to buy another in three weeks. They are not going to go down to their bank and ask for $25M in physical cash. And even at a slight negative interest rate, they aren’t going to lose too much in only three weeks. So some have to take virtually whatever the interest rate is to allow their business model to work. Every business and household has to have some level of cash or cash equivalents in the bank, so they will effectively pay a “fee” of negative interest rates for any cash holdings. But most importantly, there are major economic players who have huge outsized roles in buying and selling of assets who are not concerned with profit and loss, and that is the complex of global central banks who have been on a buying frenzy since the financial crisis. It is these buyers (specifically the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan) that have led to the negative interest rates seen in Europe and Japan. Finally, and related, some large institutions hold certain asset classes as a regulatory requirement; as central banks continue to bid up the price, they still have to buy and there are fewer and fewer of these required assets, so that exacerbates the negative trend.

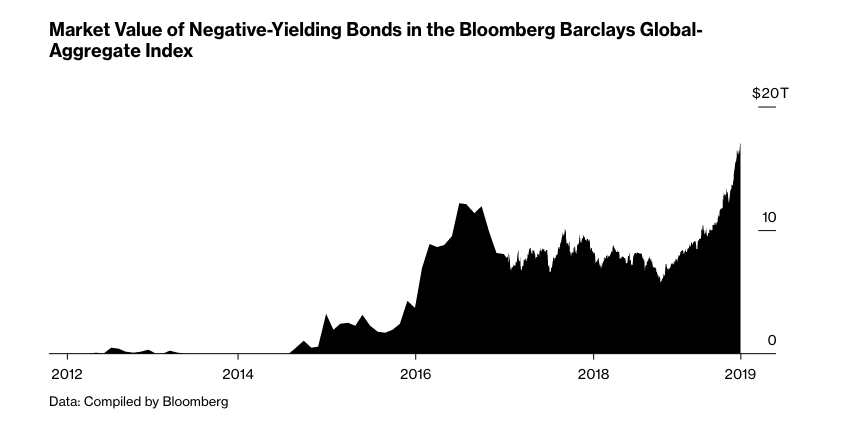

What is the scope of this problem? Well, starting from zero just a few years ago, our global central banks have orchestrated a massive amount of negative yielding assets ($17T), rapidly approach the size of the U.S. GDP:

Who is helped by negative interest rates? This is just a lower interest rate, so borrowers that are able to take advantage of lower interest rates benefit. The biggest debtor will benefit the most, if they can refinance. And the biggest debtor is the U.S. Treasury, and they can refinance, which is exactly Mr. Trump’s stated purpose in calling for negative interest rates. Further, every holder of financial assets will have the value of any future cash flows effectively increased by lower (negative) interest rates, driving asset prices up (all else equal; it is possible that negative interest rates may have other effects on future cash flows that would dwarf the interest effect, more below). But in the short run at least, it will put upward pressure on other non-cash financial assets.

Who is harmed by negative interest rates? First and obviously, those that depend/need higher rates. All savers will continue to punished, and those that do not want to go into riskier assets will be effectively taxed at a higher rate than currently. If a depositor is currently receiving 0% interest, and inflation is 2%, then they are already having a real interest tax of negative 2%. If the nominal interest rate falls to -2%, then with the 2% inflation rate the inflation tax is now 4%. 2nd and more dangerous, as we have a demographic tsunami facing us, pension funds are based on some positive interest rate. We are already having massive public sector employee pensions threatening future bankruptcy, in part due to lack of contributions made earlier based on rosy future return projections. Every pension fund is going to find their job much more difficult, such as GE announcing even our current lower (but non-negative) interest rates are going to cost them an additional $7B to fund in their quarterly earnings report. But pity the poor banker–yes the wildly vilified banker. Our entire financial system which intermediates between savers and investors is based on the “spread,” the difference between the short term and long term rates, i.e., borrow short, lend long. When interest rates are driven negative, the banking system finds it very difficult to make a profit. When banks can’t make profits, they don’t make loans, they won’t take deposits, and this is an absolute disaster. Which is why European banks are howling at the current situation and partially explains why the European banking index is trading at a multi-decade low right now. European banking is sick, we shouldn’t wish that on our banking system.

Will the U.S. see negative interest rates? A better, more accurate question is will our policy makers inflict the punishment on us that Europe and Japan are doing to their regions. Negative rates don’t just happen; they only happen because of extreme monetary mismanagement. Markets would never lead to this result*; but governments may do it to us. The Great Depression was largely the result of government mismanagement of first the international gold standard, and then the associated distortions in trade flows it created. We are currently having unprecedented monetary mismanagement by the global central banks–as if all underlying economic problems can be fixed by monetary stimulus. That is not true. But monetary “stimulus” can, and often does, lead to something far worse.

Why are we seeing the advent of negative interest rates? Per the above, this is publicly an attempt to stimulate the economy (and for politicians to boost re-election prospects), but also to reduce the cost of government and to manage an escalating debt problem that politicians are unwilling to deal with.

You and I face negative interest rates all the time; there are many items we purchase with the full realization that any future sale will result in a lower price. We might buy a new car for $30k, realizing that selling it 5 years later might result in a sales price of $15k. We properly call that consumption; it is not investment. What negative interest rates do is lower the cost of consumption, and increase the cost of savings. We really don’t need any more incentive for consumption.

* except for perhaps very short periods of extreme panic, but panics are usually the result of monetary mismanagement. Free market banking systems historically were not prone to the same level of instability as regulated fractional reserve banking systems.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach