It always amazes me that most people think that the effect of central bankers on the global economy is small. Its not just our resident critic here @ BATG. I went to a conference last year where a very conservative Christian financial advisor told me that the stock market was basically just about the great earnings. Bubble? I don’t see no stinkin’ bubble! Yet virtually daily other players say the most important thing to follow in markets is the lead of the central bankers (and oh BTW, none of these are Austrian economists).

This world is one in which central bankers are “all in,” said Katie Nixon, CIO of Northern Trust Wealth Management, on Friday. Earlier on Friday, China’s central bank cut interest rates for the sixth time since November in another attempt to jump-start a slowing economy. “Things aren’t so good in China, which is why they [central bankers] are being very proactive and very aggressive with a sixth rate cut in a matter of 12 months….So I think it sends a message to investors that central bankers will do what it takes to stabilize economic growth and to try to inflate economies.”

She is not alone; another suggests that any dips are just opportunities to buy since the central banks are basically guaranteeing the market:

Krishna Memani, Oppenheimer Funds CIO, called it an “adjustment process for the global economy that is going to take time and continue for a while.” His advice for investors is to take advantage of lower interest rates. “That means owning equities and risky assets, and when you have corrections in the marketplace, like you did in August, you have to go in a bit more,”

China is aggressively moving in their own market, and the ECB is once again signaling they will extend their QE. Even if the Fed tightens (which I don’t expect), global liquidity will continue to rise. This global liquidity tends to result in imbalances, like record debt issuance by corporations (much of this to repurchase shares of stock to artificially increase earnings per share–i.e., financial engineering).

In a similar recent post, our resident critic says:

If you believe that interest rates are “too low,” I would ask, “How do you KNOW that? ” If interest rates are too low, then you MUST have some preferred, even “natural” level in mind. What is that level? If you cannot articulate that level, then you have no reason to claim that they are too low. Too low compared to what?

I would once again refer our readers to an excellent economic educational resource, found here, 🙂 that answers this question, but I’ll copy it over for the BATG readers

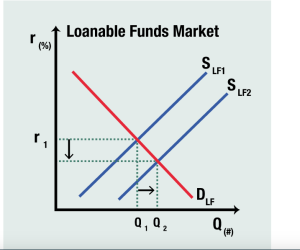

When the Federal Reserve provides additional reserves into the system, the effect on the loanable funds market is an increase in the supply of loanable funds as the Fed-created money appears to be additional savings. This necessarily lowers the interest rate. How much we cannot know, but we know that any Fed stimulus takes the interest rate below its natural rate. So our critic’s comments are misguided; there is no doubt that the Fed is artificially driving interest rates lower than they would otherwise be. A better question would be, “ok Haymond. I’ll buy that the Fed’s actions are distorting the market, but since they are always distorting the market, and we don’t always have bubbles, why are you concerned now?” This would be a more insightful and legitimate critique.

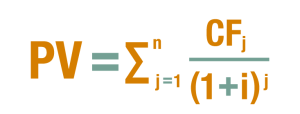

I must be much more cautious on answering this question, as we’re basically trying to ask when does the straw break the camel’s back? Or in more contemporary language, where is the tipping point? Another fundamental economic concept can help us think about this. The concept of present value teaches us that any series of future cash flows becomes more valuable the lower the interest rate, since the interest rate is found in the denominator or the equation:

When the Fed lowers interest rates, that makes every financial asset worth more (to the extent that the Fed-targeted interest rate affects the whole complex of interest rates, which is generally true). So we know that Fed policy is responsible for driving asset prices higher (which increases income inequality), after all Mr. Bernanke said this was part of his goal. So when my friend the financial advisor says that the fundamentals and earnings are driving the market, one has to consider how much of the fundamentals are simply a reflection of the artificiality of the interest rate regime? These are all counterfactual questions, i.e., they are unknown. So when does this become a bubble? My best answer is to look at this historically. I get concerned when I see financial variables go “where no man has gone before,” (yes, that’s for you original trekkies). Like the debt levels cited above. Like the Chinese market doubling in the last year (and now halving). Like the Fed keeping real interest rates negative for the last 6-7 years–something unprecedented in monetary history.

So no, I don’t know what will happen–nobody does or can. But history and theory suggest it won’t end well. Beyond the question of government management of the economy, and even beyond the bubble, I assert that there is still a question of morality: monetary policies that help those with significant financial assets while harming those that need to earn small returns on savings accounts seem to me to be unjust. But if you’re concerned about hedge fund managers, you can help them out by guaranteeing that any market instability will be met with more easy money.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach