Inside Out is an anomaly. Think of all the qualities that comprise your typical animated film and here, and not for the first time, Pixar ignores most of them. Not only does it strain convention by taking place inside the main character’s head, but Inside Out also has a dearth of singing, slapstick, and cultural references. Like Wall-E, Inside Out is determined to be its own film and nothing else and, as art, it succeeds admirably.

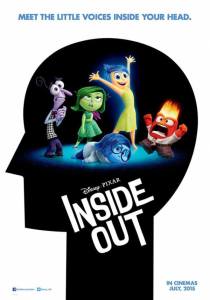

By directing Up, Monster’s, Inc, and now Inside Out, Pete Docter has helmed a handful of the best animated films. The three films are bound by uncommon characters and exotic settings. Inside Out is about Riley, our heroine who is rarely seen. Instead, we are treated to a window into Riley’s mind, especially the headquarters, where the emotions Joy (Amy Poehler), Sadness (Phyllis Smith), Anger (Lewis Black), Fear (Bill Hader), and Disgust (Mindy Kaling) negotiate Riley’s actions. Though Riley has core memories, as well as islands of habit, her emotions, with a control panel, vie to influence her upcoming actions, sometimes collectively, and sometimes while in dispute.

The group shepherds Riley through not only early childhood, where her emotional foundation is formed, but an unsettling transition across country. Due to her father’s career opportunities, Riley finds herself isolated and struggling in a new school, disconnected from friends and familiarity . Joy seeks to maintain her status atop the emotional hierarchy, but Sadness threatens to overshadow everything through her perpetual gloom. To say more of the plot would spoil the story, but the resolution is fitting and appropriate.

The portrayal of Riley’s mind is fascinating. Docter and company visualize Riley’s inner-space as made up of memories, which are formed every day and re-enforce Riley’s interests and desires. She has pockets of imagination, a corridor for abstraction, a factory for dreams, and a train of thought that connects memories to everything else. Side characters abound, ranging from little minions that clean out old memories that have faded and are no longer useful, to a cherished imaginary friend, Bing Bong, who seems to have lived out his usefulness until he is pressed into an emergency.

More than any other animated concern, Pixar specializes in emotional depth that pulls viewers down from hilarity and into tragedy, all while coiling the spring that pushes them back up again. How? By exposing characters to life in all of its unpredictability. People die. People laugh. Times are good until they are not. Days and years march along, flavored like life, in all of its sweet, delicious bitterness. Riley learns, as did Carl in Up, Andy in Toy Story 3, and even Marlin in Nemo, that even happy endings are tinged with the pain of loss and the memories of yesterdays that even when remembered, cannot be relived. Pixar refuses to view life simply, always recognizing that the human experience is fully orbed. For this alone, Inside Out deserves its place alongside Pixar’s finest films.

Though stellar, Inside Out is also a product of its time. Riley, according to the film’s conceit, acts solely based on emotion. Her memories are colored by emotion and her decisions are rooted in these particular feelings that frequently serve her poorly. Noticeably absent in Riley’s mind is Reason, or even his offspring, Will. Though Riley is eleven throughout most of the film, there is no suggestion that these emotions are stunted later on, or that adults operate differently. Inside Out is a perfect representation of how minds feel instead of think. Though it may say much about me, I perpetually remind my students that their thinking will take them farther than their feelings. In fact, reason allows us to prioritize and sometimes minimize emotion, which can be the enemy of truth. Though Inside Out never suggests it, adulthood demands a healthy subjugation of emotion. It may seem a small quibble, but I think this difference reveals much of the philosophy behind Inside Out.

Final Grade: 2.5/3 Eggheads

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach