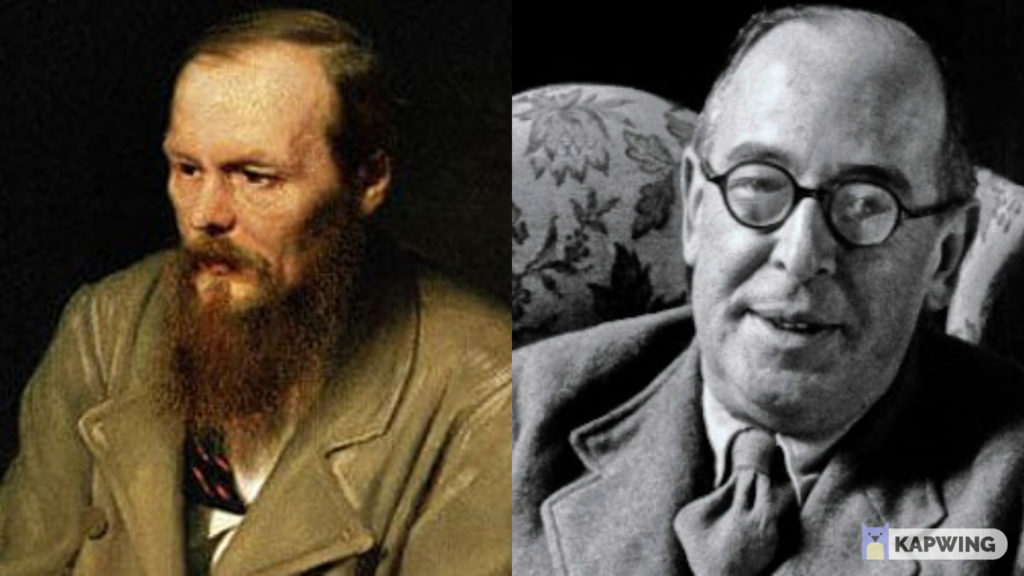

Over the course of a long weekend very recently, I found myself afforded the opportunity for a lovely visit to Hilton Head, SC with my very dear roomies (well, two of them least; the other was at some minor prior engagement, “wedding-related,” he says). If “pleasure” and “merriment” are the aim, one could do far worse than Hilton Head. Sandy beaches line the island with ample space and stunning views. The neighborhoods are well-to-do and stocked with shopping outlets, every form of entertainment, and a selection of restaurants that is to die for. One quickly discovers the phenomenon of “island time,” a sort of Venn diagram of carefree bliss, coastal dissociation from reality, and acute enjoyment of all things present. Upon returning, one has to practically reconstitute his former self in order to pick up his life from where he checked it at the door. So, it was with a slice of delicious irony that I found myself, in between gazes upon the oceanic majesty, thoroughly occupied with two books on suffering: Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky & The Problem of Pain by C.S. Lewis.

In some ways, the books could not be more different, yet the theme of suffering is ever present in both works. Dostoevsky is wholly content to take the scenic route, penning a masterpiece that layers on themes of suffering but also grace, freedom, morality, and the inexorable guilt of sin. Rodion Romanych Raskolnikov is haunted by his deeds, a man rightly condemned by his own conscience and awash in the bleak, dreary backdrop of St. Petersburg. Heroes are few, and virtue comes at a cost —the noblest of our characters, Sonya, has prostituted herself for the support of her family. Consumption takes a mother from her children, delirium drives another to death, and the air of the novel feels thick with the gray weight of anguish. What then is Dostoevsky driving at through it all?

The book reaches its zenith, I think, in Part Five when Raskolnikov confesses his crimes to Sonya. She is timid and weak in body, but Sonya’s true strength lies in her unstoppable love for humanity and a type of genuine selflessness that is nearly unbearable to Raskolnikov. He has wronged not just his immediate victims, but Sonya as well, not to mention God himself. Yet, echoing Raskolnikov from several chapters earlier, she reaches through the suffering in absolute love:

‘What have you done to yourself!’ she said, desperately, and jumping up from her knees, threw herself on his neck, embraced him, and pressed him very, very tightly in her arms.

And what then remains for Raskolnikov?

‘Go now, this minute, stand in the crossroads, bow down, and first kiss the earth you’ve defiled, then bow to the whole world, on all four sides, and say aloud to everyone: “I have killed!” Then God will send you life again…Accept suffering and redeem yourself by it, that’s what you must do.‘

It’s no great spoiler, though, [[spoiler alert all the same]] that Raskolnikov refuses this course for most of the book. Up until the last few paragraphs, even after confessing, he clings to everything except Sonya’s call to suffering and repentance. Dostoevsky’s true brilliance is to lead us so close to the brink of nihilism as to be nearly in it as our hope for Raskolnikov fades ever so dim. Yet, Dostoevsky is too Christian to let our feet slip, and Raskolnikov finds his freedom ultimately in prison, his suffering accepted and Sonya (the obvious Christ-like figure of the book) grasping a renewed man who has been “resurrected by love.”

In now to our piece steps Lewis, ever the storyteller himself, who lays aside his more-than-capable narrative senses to tackle human suffering head on with precise, tactical insight. Many of Dostoevsky’s themes find their concise, theoretical form in The Problem of Pain, yet for all the book’s brilliance, two moments stand above the rest. The first is on divine goodness, and we’ll let Lewis speak for himself here:

But God wills our good, and our good is to love Him (with that responsive love proper to creatures) and to love Him we must know Him: and if we know Him, we shall in fact fall on our faces…We are bidden to ‘put on Christ’, to become like God. That is, whether we like it or not, God intends to give us what we need, not what we now think we want. Once more, we are embarrassed by the intolerable compliment, by too much love, not too little.

Marie Miller, an independent artist whose music I highly recommend, has put it more succinctly, “God save me from what I swear I need.” Yet, we have one more note to add. In an appendix from R. Havard, Lewis directs our attention to the immense opportunity for growth found in the travails of pain. An immense, considerable pain that lasts for but a moment may reduce a man to tears, but he is rarely changed by it. But to subject oneself to the prolonged burn of tribulation…therein lies, “an opportunity for heroism.” Chronic neuroticism is the risk, a character of “tempered steel” is the reward.

So, what then for us? Two things, I believe, are to be concluded. In the first place, it is my conviction that we have done ourselves a disservice in our prayers by asking for God to take away sufferings from our lives. True enough, the desire is understandable. Lewis himself (and I would join him) was terribly disinterested in pain and suffering and called himself the basest of cowards at the prospects of it. Yet, if we take omnipotence and omniscience seriously, what then can we realistically make of the prayer, “Lord, from my shoulders, this burden lift”? Is he all-powerful? Then he certainly can do so. Is he all-knowing? Then he certainly will know when to do so. Does the Father truly love us? Then he has, at minimum, permitted this for our good, part of his “intolerable compliment.” It seems to me that our prayers, then, should not be aimed at the release from our sufferings but at a serious and fervent call for the strengthening of our bodies and souls through suffering. When the time is right, rest assured he will permit it to pass; we needn’t remind him.

Second, having redirected the efforts of our prayers, I wonder if perhaps we may better reconcile the tension between Christ’s call to yield our yokes to Him while in the same breath he bids us to take up our crosses and follow Him. Raskolnikov’s freedom is found in accepting his suffering, not for suffering’s sake alone, but that God may give him life once more. The Father’s will is for life, not death; remember the suffering that produces death is not from him, only that which leads to repentance and life.

Let us hope then for repentance and the godly sorrow which produces it. Let us accept the present, actual trouble, knowing that God will give us life anew. In laying down our old natures and joining in the sufferings of Christ, may we then reach Dostoevsky’s conclusion:

…here begins a new account, the account of a man’s gradual renewal, the account of his gradual regeneration, his gradual transition from one world to another, his acquaintance with a new, hitherto completely unknown reality.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach