Gallup polling this week showed that the credibility of the Federal Reserve is down to 36% (those that have a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence)–the lowest level since Gallup begin tracking. To be sure, as Gallop notes, this tends to track overall economic performance. And most people are particularly pessimistic about the economy, given the reduction in real wages from the inflationary binge our government inflicted upon us. Berean readers know that I’m a harsh Fed critic, but the general public continues its rational ignorance about the Fed, until the Fed really let’s things get out of hand. Inflation is one of those things that really focuses general public’s attention. Economists often talk about confidence (in the Fed) in terms of expectations–how does Fed credibility affect peoples’ expectations of the future. This is one of the biggest lessons learned following the 1970’s Fed-induced inflationary debacle–when inflationary expectations are allowed to “bake in,” with the Fed having little credibility, the costs to right the economy can be massive. While the Fed perhaps deluded even themselves with this idea of inflation not being a problem, and then only transitory, they now have awakened as if from a deep nap and remembered the pain of the 1970s and subsequent sacrifice ratio’s required to disinflate. Further, Jerome Powell is a serious man and well understands the difficulty he faces. I’m sure he is professionally embarrassed by allowing inflation to get where it is. I think we can trust his words that he does not intend to let inflation bake into the system. The problem is that the Fed historically keeps policy too easy too long, and then over tightens–we get a boom and then a bust. We’ve had the inflationary boom. Can we avoid the recessionary bust?

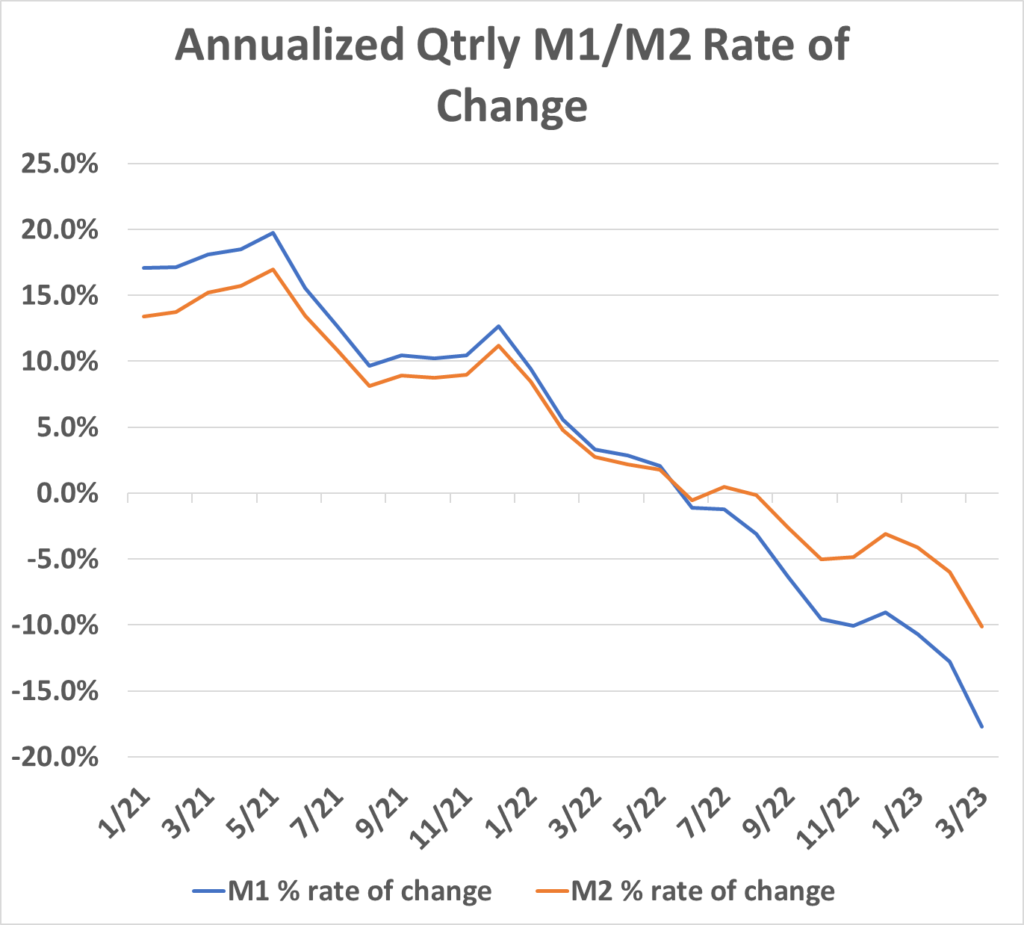

Since the Fed ended its bacchanal money printing party in Mar ’22, it has aggressively hiked interest rates (the fastest rise in short run interest rates in U.S. monetary history)–now over 5%. Further, it has continued to shrink it’s balance sheet meaningfully. The bank panic two months ago saw a short sharp reversal to its balance sheet reductions as the Fed quickly acted to stem the panic, but that is now being reversed. Overall, money growth in the financial system continues shrinking at a fast pace, as seen below.

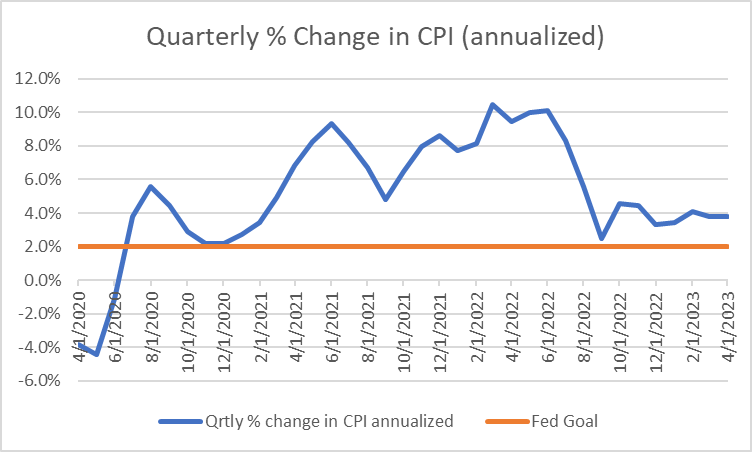

If we were in normal times, this rapid deceleration of money growth would herald a depression of significant magnitude. But these are not normal times–the after effect of the prior monetary binge lives on. Nevertheless, the worst of inflation is behind us. Today’s headline CPI number of 4.9% annualized inflation masks the significant slowdown in inflation, as seen in my calculations below (calculating the annualized inflation rate quarterly) :

Allowing the data to be calculated on a quarterly vs annual basis allows us to see inflation a bit more granularly. As the chart shows, we’ve been down around 4% for eight months. To be sure, this is still double the Fed’s goal of 2%, but it is a far cry from the 8-9% that was so punishing in 2021 and much of 2022. And a good bit of this inflation (certainly this month’s) is from housing, which tends to be a lagging part of CPI (as leases are usually renewed annually). I don’t see inflation rising going forward absent a reversal of current Fed policy, and indeed, I expect it to continue lower as the economy weakens.

With this in mind, I think it is time for the Federal Reserve to pause its tightening. We know monetary policy operates with “long and variable lags.” It seems prudent to see how the banking system and firms adjust to higher rates. Many firms levered up with cheap debt over the last few years; as this debt rolls over at higher rates profits are going to be squeezed. Further, while the first few bank failures were poorly managed and not diversified, every bank has some of the problems of liabilities significantly more costly, suggesting loan activity will decrease. The worst thing would be to throw the economy into a steep recession and then take interest rates back down to zero. The goal needs to not only be to get inflation down, but also to normalize monetary policy with short term rates in the 2-3% area and long rates in the 4-5% range. The Fed should keep rates steady (I would not have raised the last time) while continuing their reduction in their balance sheet. Reducing their balance sheet is sufficient tightening to preclude inflationary pressures from building up further, as the money supply data above strongly suggests.

We have a very steeply inverted yield curve already, with short term rates significantly above long term rates. The whole banking model is to borrow short and lend long, with a positive spread between those two. An inverted yield curve thus makes it very difficult for banks to profitably find investments that exceed the cost of their liabilities that fund investment. Every additional uptick in interest rates increases the depositor’s incentive to take their money out of the bank into a higher yielding asset (e.g., MMMF), which potentially causes more bank failures. It’s time for the Fed to strategically pause. If the Fed handles this right, they may just be able to restore some of that hard-won credibility that Paul Volcker created forty years ago.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach