First up is the ongoing failure of Keynesian economics with its calls for government stimulus to save the day. Japan is the case study for looking at what government policy makers have done. Ever since their stock bubble burst (enabled by easy money policy) in the late 80s, the Japanese economy has went from one period of government “fix” to the next. The end result has been 25 years of relative stagnation and their national debt is now double ours at >200% of GDP.

source: tradingeconomics.com

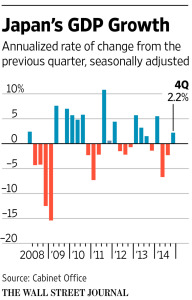

In what I consider the ultimate in economic ignorance, their latest effort is to force their consumers to pay more for goods and services. That will boost their economy–yes a deliberate policy of inflation. Last year’s unprecedented QE (greater than ours relative to the size of their economy) was an attempt to boost their stock market and stimulate consumer spending ahead of price increases. It didn’t work, in part because there is no free lunch: to pay for the stimulus efforts the government passed a large sales tax. The result?

Sharply lower oil prices have also frustrated the Bank of Japan ’s efforts to achieve 2% inflation—a key policy goal. The core consumer-price index—stripping out food prices—fell to 0.5% in December, excluding the sales-tax increase. That was the lowest level in 16 months, and some economists say the central bank, which holds a policy meeting this week, is likely to introduce further stimulus in the coming months.

Really? Lower oil prices bad? For an economy that imports virtually all of their oil, a drop in oil prices is an unmitigated blessing! Yet Keynesian thinking would turn a blessing into a curse.

Next up is the European Central Bank’s monetary magic. Mario Draghi is in favor of the same monetary debasement that Fed and the Japanese are doing–since its obviously been so successful here and in Japan. Or is there an ulterior motive? Say’s Mr. Draghi,

All monetary-policy measures have some fiscal implications.

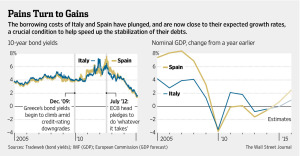

Vera Smith, in her 1936 classic The Rationale of Central Banking, shows that the institution of central banking always has one underlying objective: enabling stable, cheap public finance. The central bank is first and foremost the bank of its sovereign, and every customer wants the cheapest terms possible. As the chart below from the WSJ shows, Mr. Draghi’s policy is making it easier for Greece and others to avoid the difficult choices necessary to get their public finances in order.

Finally we have Walmart. Much is being made of the decision to raise wages going forward (heading to $10/hr next year). Did they capitulate to public pressure? Was it a fear of unionization? Are they doing it as a public relations move? Here is my simple conclusion (which is not particularly insightful): they did it because it was in their interest. Could be all of the above. Walmart is likely responding to their need to compete for a higher quality worker to improve their customer’s overall shopping experience. Walmart also has significantly higher turnover (and associated training costs) than firms such as Costco and Whole Foods, which pay a much higher wage. The economic concept of “efficiency wages” suggests that it is often in the interest of firms to pay above market wages in order to get both above average worker quality and effort. That seems to me what Walmart is trying to do.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach