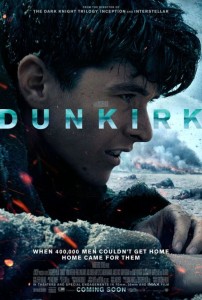

Turning the battle of Dunkirk into a film presents obvious challenges, for it was less a battle and more a retreat. Filming a strategic withdrawal that occurs at the beginning of a protracted war harbors no obvious moments of glory and only a muted climax. Christopher Nolan, the director and obvious driving force behind the entire production of Dunkirk, is more than up to the task.

Turning the battle of Dunkirk into a film presents obvious challenges, for it was less a battle and more a retreat. Filming a strategic withdrawal that occurs at the beginning of a protracted war harbors no obvious moments of glory and only a muted climax. Christopher Nolan, the director and obvious driving force behind the entire production of Dunkirk, is more than up to the task.

Dunkirk weaves three separate strands of narrative. The Mole (the soldiers on the beach and the sailors trying to evacuate them), The Sea (ships big, and mostly small, trying to connect Britain to its beleaguered troops), and The Air (where Spitfire pilots try to ward off attacks) all work together to tell a big story through small eyes. Nolan shows how these elements interacted not only thematically, but actually. Tommy (Fionn Whitehead), a green soldier just wants to live and relies on methods sometimes honorable and sometimes dubious to do so. Mr. Dawson (played superbly by Mark Rylance) captains a tiny ship, as part of the government’s plan to rescue soldiers unconventionally, and has his son Peter (Tom Glynn-Carney) and family friend George (Barry Keoghan) along to help in the journey. Mr. Dawson steers into the waters aware of what could happen, but he sees the journey as a duty where danger must be endured instead of avoided. Farrier (Tom Hardy) and Collins (Jack Lowden) take to the skies in small planes with limited fuel, essentially unaware of what they might find, but hoping to ward off German air attacks against the largely naked troops and the ships trying to save them.

As a film, Dunkirk is a triumph of skill and artistry. We have all seen ships sinking, planes burning, and bullets flying on camera. Nolan manages to make it all fresh and remarkable. The camera work puts the viewer in the cockpit as planes drop toward an unforgiving sea, below the waterline as a ship fills far too quickly, and in a desperate crouch hoping thin cover is enough to shield your flesh from hard and fast machine gun fire. Nolan proves that tension and dread do not require gore and that suffering can be seen and felt even when limbs are not flying off and innards are not spilling onto the deck. Nolan, like few before, communicates the emotional trauma of war while sparing us of its graphic reality. Beyond all of this, Nolan films the human condition, which shows itself in conflict. We see treachery, bravery, guile, cunning, and shock spill across the screen, sometimes on the face of the same character. Nolan also frames beauty from ashes in a manner too often absent from war films, a reminder that soldiers are fully human, not just narrow beasts.

Aside from the visuals, Nolan uses sound brilliantly. Hans Zimmer’s score is highlighted by a ticking stopwatch, which reminds listeners of the split seconds that separate life and death. Characters dip into the ocean to escape a strafing run, only to be aurally buffeted by explosions nearby. Rounds ricochet around pierced hulls. Adding to the realism, dialogue is often drowned out, and conversations are obscured. Sometimes, the sounds of chaos reign.

The actors are outstanding, even if Dunkirk is not an “actor’s film.” There is little focus on personalities. We know next to nothing about backgrounds or futures or distinguishing characteristics. Dunkirk is plot-driven and it rarely rests long enough for conversations, so the acting is usually reacting to unfolding events. Here, the cast does much with little. Kenneth Branagh (Commander Bolton) is one of the few recognizable faces. He patrols the shoreline, as the highest ranking officer on the scene, with menace and humanity, but he earns his salary when the camera captures his face as he beholds the monstrosity of a ship sinking just a few feet away.

Fascinatingly, Nolan assumes his audience either knows something about World War II or he calculates that particular knowledge is not critical for audience appreciation. Nolan drops the viewer into the retreat with a few general lines of text and a bare map to illustrate minimal geography. It is clear the British and French are panicked and vulnerable, pushed to the beaches, hoping a skeletal rear-guard will be enough to protect several hundred thousand soldiers trying to get home, not to take comfort in peace and loved ones, but to continue their fight. After all, there are many miles and millions of casualties between Dunkirk (1940) and Berlin (1945). We see the film with an understanding of who wins in the end. There is hope for the future, but it is dimmed by the costs victory extracts.

Dunkirk, as a film and an event, presents an unusual melding of the front and the homefront. Britain faced a giant conundrum. With a massive, isolated force so close to home, but stranded nonetheless, the government worried about committing more resources to a dire circumstance. Sending a large force of planes and ships to evacuate the stranded soldiers also put those precious resources in harm’s way, precisely at the moment Britain had to contemplate a possible invasion. At this time, Britain had not come close to solving the German U-boats and the Blitzkrieg. Though an Empire, Britain was an island nation. American entry was more than a year away.

As a stopgap measure, the government mobilized the civilian fleet. Given the slight distance between Dunkirk and the British coast, even recreational sailors could pop over and ferry a dozen or two men to safety. Of course, this also meant that such vessels were now themselves targets for the Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine. In a very real sense, fathers and brothers prepared to die in order to save their sons and siblings, flipping the narrative that is so familiar in most war films. Dunkirk, unlike other films, breaks the illusion of war, that there is a separate price to pay for the homefront. There is one price for all, be they in the battle or sitting before a dwindling hearth hundreds of miles from the front or, in this case, sailing a family boat into hostile waters reserved for warships. Everyone suffers in war, and Dunkirk capitalizes on that reality brilliantly.

Expect Dunkirk to be a favorite come award time next Spring. The film should take its place among the best war films ever made.

Grade: 4/4 Eggheads

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach