It was late August of 1998 when I arrived in my first class of graduate microeconomics at George Mason University. I arrived early, and waited with eager expectation for the professor, who was one of the two professors that had drawn me to GMU–Walter Williams. When he walked in, it was clear who the dominant figure of GMU’s econ program really was–a towering 6’6″ man with a bold confidence that yet was open and gracious. He made clear why he was there, and why we were there. He was there to ensure that every single GMU Ph.D. would have mastered the fundamentals of economics–that in an age where many thought economics was all about the analytical tool kit, e.g., applied econometric techniques to validate abstract models, Walter would ensure that we understood scarcity, and the pervasive nature of tradeoffs, and how relative prices and decisions at the margin drove everything. Yes we had to do partial derivatives and use the Lagrandian. But those tools were applications to illustrate the fundamental nature of the necessity of tradeoffs, which were the essence of microeconomic analysis. Mixed in with economic concepts were constant illustrations of his life with Mrs. Williams, who was the object of his incredible affection. Walter’s true genius and gift was not the significant intellectual contributions that most great economists make, but that he had the unique ability to take incredibly complex issues and boil them down to the essence of the issue in everyday language. He was, as he liked to say, the people’s economist.

Walter was the towering figure of my time at GMU, and I considered myself triply blessed: Walter brought the best of UCLA microeconomics (studying under Armen Alchian and Harold Demsetz), James Buchanan brought Chicago economics (and his professor, Frank Knight) to bear, and Pete Boettke was the Austrian energizer bunny. But Walter set the tone in the School as the Chair of the Department, and he clearly did not Suffer Fools. He would walk around with the U.S. Constitution in his pocket, and he would remind idealistic students of how incredibly rare liberty was in all of history. Although I only got to take one class from Walter, he is now etched in who I am. And I am one of the hundreds if not thousands of graduate students that he poured into. And then there are the millions of people that avidly listened to him when he would guest host on the Rush Limbaugh program, or when he would debate on PBS. Or the millions that would read him as the most widely syndicated economic columnist in the country. Talk about a towering legacy–Walter Williams will continue for generations to cast a long shadow.

As I remarked last night to my wife, all my heroes are now passing away. It’s not surprising; I’m getting to be upper 50s, and my heroes are from the previous generation. The certainty of death that comes to each one of us is the constant reminder that this life is fleeting, and that eternity awaits. And that leads to those great questions of life, which are ultimately only answered in Jesus Christ and His work on the cross. The world today will honor and give homage to the life of Walter Williams. And we well should. But let us remember that every one of our heroes will meet our maker, the true hero of our story, and that in our brief moments on this earth we live to serve Him and others. Walter Williams served me and millions of others well; I pray that this day finds him rejoicing with Mrs. Williams and the one true King.

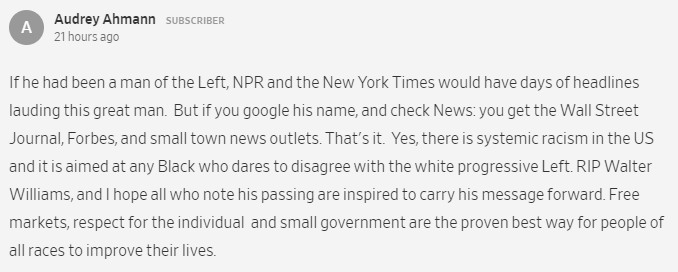

Edit Update: This comment on the WSJ obituary written by Don Boudreaux is worth sharing:

Well said, Audrey!

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach