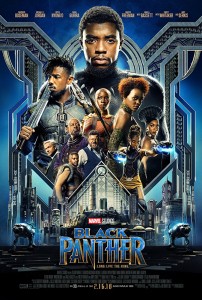

It should not surprise us that a film called Black Panther (directed by Ryan Coogler, and written by Coogler and Joe Robert Cole), has more than a political bent. The comic book character was created in 1966, which was an audacious moment for his debut. Though Stan Lee, a co-creator, has denied any connection between the incipient political movement and his superhero, an African prince with supernatural powers, the coincidence surely shapes how we understand the comic and now, to a lesser extent, the film that bears the name.

It should not surprise us that a film called Black Panther (directed by Ryan Coogler, and written by Coogler and Joe Robert Cole), has more than a political bent. The comic book character was created in 1966, which was an audacious moment for his debut. Though Stan Lee, a co-creator, has denied any connection between the incipient political movement and his superhero, an African prince with supernatural powers, the coincidence surely shapes how we understand the comic and now, to a lesser extent, the film that bears the name.

Make no mistake, Black Panther, like some of the great comic book films of the past year (Logan and Wonder Woman), has something to say. The story is cracking all on its own, but it is a framework for a clear set of messages.

T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) has assumed the throne of Wakanda after his father’s death (as seen in Captain America: Civil War). Though it appears an impoverished third-world country to outsiders, Wakanda is actually a wonder of technology fueled by its vibranium harvesting. In fact, its technology is so advanced the nation is able to hide in plain sight. Only Wakandans are aware of the near-magic the nation possesses. Medicine, communications, aviation, and weaponry are just some of the advanced industries we see in Wakanda.

T’Challa is aided by a love interest, Nakia (Lupita Nyong’o), who works outside Wakanda as she tries to aid Africans suffering at the hands of warlords and terrorists. T’Challa wishes her to be his queen, but she demurs. His military leader is Okoye (Danai Gurira), a warrior loyal to Wakanda above all other claims and relationships. His real secret weapon, however, appears to be his sister, Shuri (Letitia Wright), the guru behind Wakanda’s most recent advancements.

The central conflict in the film begins when an interloper arrives at the Wakandan border bearing an unorthodox gift. Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) is an American through and through. A trained covert operative, Killmonger makes a claim to the throne. His claim has enough merit to warrant a battle of arms with T’Challa.

The two men dominate the film with their talent and physical presence, but it is their worldviews that drive the film’s ideas. Killmonger looks across the continent and the world to the plight of Africans, wherever they find their home. They have been enslaved and ensnared, subjected by societies that use and abuse them. In the face of the African diaspora, Killmonger brings a message of hope and deliverance at the tip of a sword sharpened by Wakandan technology. He preaches liberation and eventual dominance, “where the sun will never set on the Wakandan Empire.” T’Challa answers his cries with diffidence. Nakia pulls him toward engagement with the world, while his family and responsibilities drive him toward “Wakanda First.”

Some will be tempted to read Wakanda as the story of African Americans, especially during the turbulent civil rights revolution of the 1950s and 1960s. Martin Luther King, Jr., urged his followers to use the system in place to achieve their political goals (though he was willing to subvert that system through non-violent protest), while others, like Malcolm X, at least earlier in his public career, railed against integration. He favored black supremacy. There is likely some truth to this reading, but it feels a bit cramped. African Americans were never in a position of authority or power. They argued over how to bend a system that disfavored them. To work with the powers that be or overturn them? That was the question.

Black Panther begins from a point of supremacy. Black Panther is more accurately about the use of superior power in an unjust world. There is horror, immorality, and evil. How best to respond if given the chance? Do you tend your own garden while keeping your hedges high or pry open your gates to the benefit of others? In this sense, and this is likely because of my time and place, Black Panther is a racially tinged take on America in the Age of Trump. Though it might be inaccurate to claim we still live in a unipolar world, how should we respond to a messy, unjust, fallen place when we have at least some of the tools needed to clean it up? Do we build walls and hide in plain sight or build bridges to the benefit of all?

Erik Killmonger is the best villain of the Marvel Cinematic Universe–not because he is especially vivid or colorful or powerful, though he is all those things. He is sympathetic because he seeks justice, even if his forms are twisted. He is complicated and at times blindingly right. T’Challa is also his ideal foil. Wise but not arrogant, powerful but not abusive, T’Challa’s seeming perfection gives way to his dangerous search for prudence. The crown is oh so heavy as it settles onto a young man prepared for life to wear it, but still unsure of its fit.

Like The Dark Knight, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Logan, and Wonder Woman, Black Panther is not just an excellent comic book film, it is an excellent film. There is no need for a modifier. Black Panther is the kind of film that will grow the genre away from its sometimes schlocky roots and toward the art all films strive to be. See it.

Grade: 3.5/4 Eggheads

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach