***This review, especially starting in the seventh paragraph, is written for people who have seen the movie, or for those who don’t care about spoilers.***

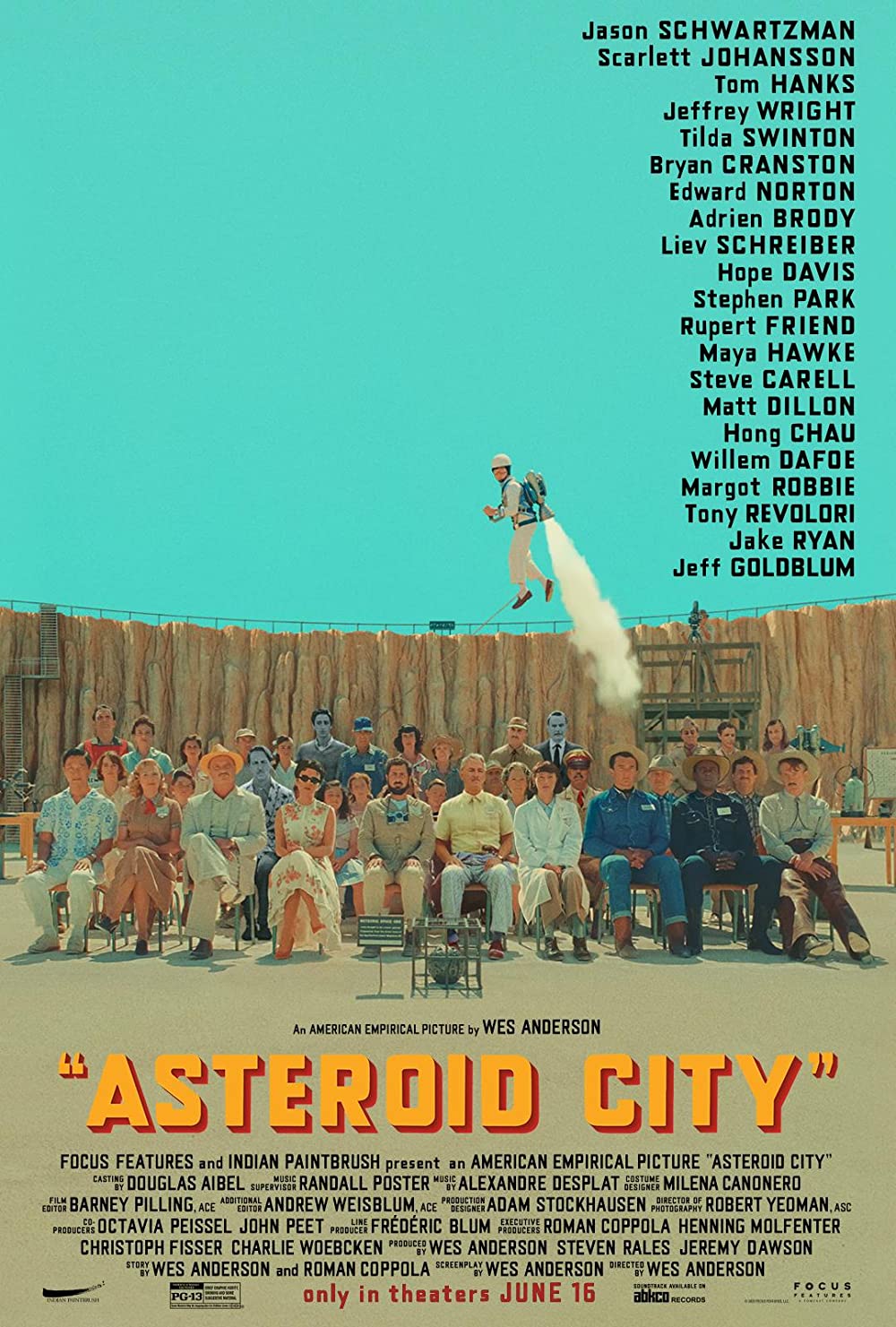

Asteroid City (2023) bears all the marks of a Wes Anderson film. The compositions are deliberate. The colors are striking. The dialogue is direct and sometimes lacks subtlety. The characters are suffering, but their sense of style always keeps them emotionally removed, not just from us, but themselves. The soundtrack is catchy, and just a step away from obvious. I find Anderson’s movies thoroughly charming, and among my favorites, though they are often empty calories–visually pleasing, but lacking nutrients for the mind.

Unlike the rest of his films, here, Anderson’s cool detachment melts under the harsh, unforgiving desert sun. For maybe the first time in his career, the director asks, and tries to answer, a fundamental question. How do we live in a world beyond our control, where random acts of kindness and terror stand just offstage, waiting to enhance or spoil a perfectly delivered line?

Asteroid City is a small western town, baked into an overwhelming landscape. Its claim to fame is an asteroid that, several thousands of years ago, formed a crater in the village. A diner, gas station, and a motel of cute, detached bungalows, have grown around the landmark. Asteroid City hosts an annual festival that consists of astrological observations, tours of the crater, and recognition of outstanding “junior stargazers,” who bring their inventions for the military, a company, and indulgent parents to see. The year is 1955.

On the cusp of the festival, a broken down car is towed into town, and it carries our lead, Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), a war photographer, and his four children. His oldest, a genius named Woodrow (Jake Ryan), has invented a machine that allows him to project images onto the moon’s surface. His young daughters, though perhaps equally brilliant, are bent toward darker things, imagining themselves as knee-high witches and vampires. Other junior stargazers, and their parents, spill into the proceedings, including Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a famous actress, and her daughter, Dinah (Grace Edwards). Her invention causes rapid plant growth, but any resulting fruits and vegetables are toxic. Other inventions abound, including a death ray (that never kills), and a jet pack donned by a teenager but tethered to an adult. The parents and children are joined by the innkeeper (Steve Carell), who seems almost to embody the town, Augie’s father-in-law (Tom Hanks), the local scientist (Tilda Swinton), a general (Jeffrey Wright), a traveling teacher (Maya Hawke), who exhorts her willing students toward regular prayers, a country troupe that missed a bus, and many more peculiarities.

The junior stargazers and their parents get to know one another, awkwardly and then more intimately. Some are charmed by the desert and consider settling there. Others are bound by the pain of loss, the possibility of love, and hopes for the future. As the competition moves toward completion, the story takes a radical turn, and all the characters are confronted by a new reality. This changes some forever, and others not at all.

This is the moment that Anderson begins to ask larger questions. What is human life in the face of a universe so vast and wild? What if everything you thought you knew was wrong or, merely, out-of-date? Anderson’s answers to these questions are real but incomplete. If his search for meaning has concluded, the blackness of space is a void and he finds an artistic comfort there, but as beautiful as his comfort may be, it leaves me cold.

***Spoilers Ahead***

This story, which is perfectly pleasant and interesting, is artifice, the show within a show.* In-between acts, Anderson introduces us, through his narrator (Bryan Cranston), to a playwright (Edward Norton), an actor/director (Adrien Brody), a drama teacher (Willem Dafoe), and some of the Asteroid City cast in the guise of the actors playing them. These black and white interludes are jarring next to desert hues, and their tone wavers between matter-of-fact and melancholy. These characters are striving to create–by word and deed–“Asteroid City.” They fuss over casting decisions, scenes that have been cut, and the mannerisms they bring to their roles. At one point, Augie Steenbeck, the character, trundles through a set door, and the penetrating yellow and beige of Asteroid City drain into the grey doubts that threaten to suffocate his performance. All of these splices of life are about artistic struggle of one sort or another. These characters are searching for the fuel that opportunities, inspiration, love, and confidence bring to a life devoted to craft.

Here, we find, Anderson’s answer to the presence of the thin, shy space alien that disrupted Asteroid City. Like Augie’s pictures, that always turn out, Anderson’s worldview is settled. Art, for Anderson, is the struggle against the unpredictability of life. Asteroid City, the production, is shot through with death, both real and implied. Several characters are always armed. A seemingly random police chase between a hot rod and a squad car being trailed by police motorcycle is scored by a melody of exchanged gunfire. This happens several times and no one bothers even to mention it. Atomic bomb tests, close enough to see and feel, bookend the proceedings. Augie’s wife is dead and gone, a victim of chronic disease. His daughters ache to resurrect her with a spell. Death is so close that a ray, invented by a child, would need a but a mere flick of a finger to disintegrate a person.

Against the horror’s of life–the absence of a God, the presence of death, and the clumsy lurch we all make toward love and connection–Anderson, and his characters behind the play, pursue art. Art, for Anderson, shields him enough from the reality of the abyss that life becomes bearable. Art, for the artist and the consumer, is the dream world where anything is possible, and it stands in sharp contrast to the hopelessness of life. This is why Asteroid City is beautiful and vibrant, while the vignettes are flat. This magical realm doesn’t just settle on us; we must pursue it. After all, Anderson tells us in so many ways in this film, “you can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.” We must consciously decide to sleep so we might dream.

Asteroid City was penned during the COVID quarantine, or at least against the backdrop of the pandemic. As the characters in the film struggle with their own quarantine, they are left with little to do but contemplate their fates as the world they were accustomed to was shattered. For us, during COVID, hugs of affection were forbidden or loaded with dread. Weekend jaunts to new places were out of the question. A meal with new or old friends was impossible. Death tolls spiked. Morgues were piled high. Two weeks became two months and the specter of two years felt likely. I believe Anderson spent that time arriving at an answer, at least in his own mind, to the questions prompted by an upside-down time and place. I can’t agree with him, but I admire his effort to grapple with hard things.

I enjoy art and feel some kinship with Anderson’s hope that art can bring us succor during dreaded days. But art only brings full glory when it lifts our eyes toward God. In him we find answers. The universe is not cold and empty, but, even marred by human sin, a product of the warmth of his love. Art can spark real emotions that move us, but the shadows of our emotions must always be illuminated by the light of God’s revelation. This does not make the Christian life easy or simple. It is still hard and laced with suffering, just as Anderson thinks, but we suffer, in the end, for the glory of the God who gives us hope. We don’t need to be shielded from reality because we have been redeemed from the chaos of sin. For Anderson, art is a true escape from the end that reason brings, but for believers, it should evoke a feeling that binds the whimsy of our hearts to the divine truths that live in our minds.

*The Anderson critic might yawn and say, “yes, just like the rest of his films.” There is truth to this. Anderson has never been searching for verisimilitude. His films are deliberately artificial due to his nostalgia or idealism. I think such concerns are largely made of straw men, like whining to George Lucas that lasers don’t make sound or the Death Star would be impossible to build (either due to money, resources, or physics). I willingly grant the artifice at work in Anderson’s films, but Asteroid City seems deliberately, comically artificial, and I think that fits into his larger purpose here. The year is 1955. There are no African American generals in the military, and none of them give speeches that reside between beatnik poetry and Aesop. Native American soldiers, with braids hanging out of their shiny helmets, did not exist in that fashion and would never hand a rifle to a boy. Dr. Hickenlooper is a couple decades early. This is a chosen fantasy, more extreme than his other films, primarily to make his point about the rest of his films. Obviously, no film is real in a literal sense. Movies are produced to bring us escape, to one degree or another–either to escape from our dreary lives into something fantastical and mesmerizing, or to escape our peaceful lives of privilege to experience something much harder and more challenging. Anderson’s films generally do the former, while this one is designed to do the latter.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach