First, I am a Colts fan. I grew up in Indianapolis and generally despise the Patriots, not because they are successful, but because their success has so often come at the Colts’ expense. More than any other team, New England has stood in the way of the Colts winning more Super Bowls.

Second, the Patriots are just better than the Colts. They are better schematically and they are better defensively. They are so much better right now that the presence or absence of deflated footballs had to have precious little to do with the game’s outcome.

Third, I think the entire controversy over the deflated balls at the AFC Championship game is overblown. Then again, sports coverage in general is overblown. I love football, but our culture’s obsession with it is sometimes unhealthy. I loathe to contribute to that sensation, even on this little, non-sports related blog.

All that said, I do find the following analysis very interesting. Warren Sharp, over at Slate, has run some numbers on how the Patriots have performed against the rest of the league in fumbling the football. It is fairly well established that football turnovers are, to a high degree, randomly distributed. Teams are very unlikely to sustain any consistency when it comes to recovering turnovers.

Quarterbacks and teams do have control over their own turnovers to a degree, especially as it relates to interceptions. Fumbles, however, are a different animal. They are the product of factors often beyond the players’ and coaches’ control. The right hit at the wrong moment and the weather can be prepared for, but not controlled.

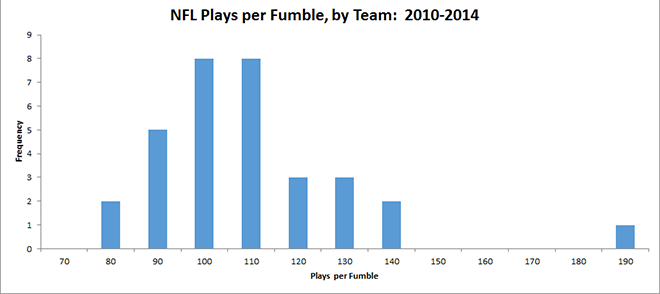

Sharp argues that the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that the Patriots have been historically good at not fumbling during the past five seasons, both in relation to the rest of the league and past teams as well. Here is one chart (among several) that shows his reasoning.

The figure shows the number of plays run/fumbles lost by team from 2010 to 2014. This means that the statistic controls for the team’s pace by not looking at the total number of fumbles, which would be skewed against the teams that run more offensive plays, and therefore by definition more likely to have turnovers, but by looking at the rate of fumbling. The average team runs about 105 plays/fumble lost. The Patriots were at 187 plays/fumble lost. As you can see, that number, all the way over on the right of the distribution, shows how far the Patriots are from the average. Most teams are within a tight band around the mean. The Patriots appear to be several standard deviations away from the mean.

As an expert that Sharp consulted with put it, assuming that fumbles are normally distributed, the Patriots’ performance here is equivalent to winning a lottery where your odds are 1 in 16,000. Not impossible, obviously, but very far from coincidental.

There is much more evidence he examines, so don’t take this figure as the summation of his argument. He concludes, however, that the Patriots have had a historically low rate of fumbles lost. It should be noted that the Patriots are also unusual when you examine the data for fumbles and not just fumbles lost. Here, the Pats are far and away the best outdoor team, performing similarly to dome teams who play half their games, at least, inside a controlled environment.

To be fair, you have to consider other factors that might lead to such low rates of fumbling. As Sharp notes, perhaps the Patriots call plays that are less likely to lead to fumbles. Perhaps they look for, and retain, players who are especially unlikely to fumble. Perhaps they coach a special technique that lowers the probability of fumbling. Or, perhaps they play with deflated footballs that reduce the incidence of fumbling. Or, of course, it could be a combination of all these factors. It could also be true that Sharp’s data are mangled, but they do not appear that way, at least on the surface.

This is inferential evidence, to be sure. The data also do not prove a causal connection, but the data do suggest a relationship that should at least be considered as part of the evidence of what is happening.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach