Seventeen Republicans have thrown their tam o’ shanters into the presidential ring and as we just passed Labor Day, the race is still in flux. Expect it to stay that way at least until January, and even then, there will be movement and surprises.

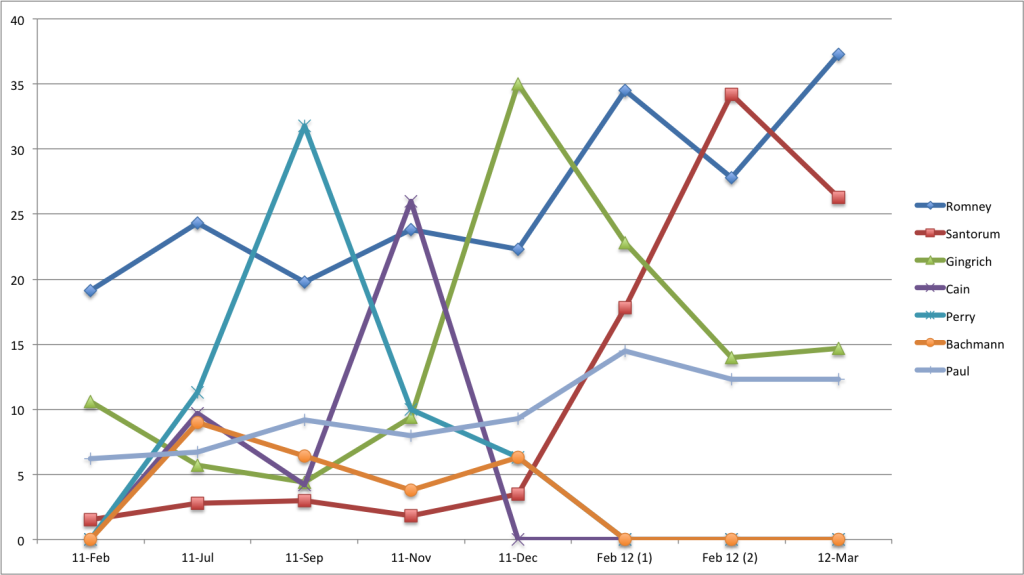

The figure above is a rough sketch of average polling numbers among Republicans during the 2012 cycle. The data come from polling averages as collected by RealClearPolitics. I selected a few months just for the sake of comparison. The figure begins with February of 2011 and ends in March of 2012. This captures the entirety of the “invisible primary,” where no votes are cast, but where fundraising, organizing, and jockeying take place, and the beginning of the actual primaries. Not all of the Republican candidates are represented, but the key players are–Romney, Santorum, Gingrich, Cain, Perry, Bachmann, and Paul.

The field began with Romney in the polling lead. This fits a standard Republican pattern dating back at least to 1980. The Republicans love to elevate the previous cycle’s second place finisher into the nomination. Reagan (1980), G.H.W. Bush (1988), Dole (1996), McCain (2008), and Romney (2012) all secured nominations after being the runner-up in the most recent competitive primary. So, it appears to be Romney’s turn, right?

Eventually, it worked out that way, but look at the tectonic shifting that took place. At different points, Perry (Sept. 11), Cain (Nov. 11), Gingrich (Dec. 11), and Santorum (Feb. 12) were front-running, at least according to the polls. Even Bachmann threatened double-figures, and Paul finished progressively stronger, though he was not able to build on his base enough to scare the leaders.

There are different sorts of presidential primaries. Sitting presidents are rarely challenged, so the primaries become a roving coronation that climaxes at the convention. Other primaries come down to two major figures and are more predictable or at least stable. In multi-candidate affairs, especially with no obvious front-runner, volatility seems to be the only constant. Voters are not necessarily engaged, and while there are large exceptions, average citizens know little about these candidates, who often struggle to distinguish themselves from one another. Name recognition drives some of this, of course, as people often state a preference based on that fact alone.

What was true in 2011/2012 may be doubly-correct in 2015/2016. With seventeen announced candidates, voters may be gravitating toward Trump because they know who he is. This does not explain how Carson, Cruz, and Fiorina are making inroads. They are succeeding, I think, because they are identifiable in important ways. Carson is the only African-American in the field, and Fiorina is the only woman. Cruz is an ideological flamethrower who turns red meat into delectable treats. This is not intended to downplay their strengths, which are considerable. Also, they are relative outsiders, and the American electorate, at least at the moment, is bending toward change.

Trump’s most astute move has been to use immigration has his wedge issue. More than probably any other topic, immigration exposes the gap between voters and office-holders. Our ruling elite has largely coalesced around relaxed immigration laws, regardless of their rhetoric. Voters simply do not agree, but since the party elites are relatively united on this, there has been no viable outlet for those voters. Trump is that outlet, while many of his opponents are perceived as part of that disconnected elite.

So far, this has all hinged on polls, which garner an inordinate amount of attention because they make for easy news. After all, horse races are exciting. Polls fail to capture more concrete indicators of strength. Fundraising is key. Campaigns will not file their quarterly reports until next month, so it is hard to know where the field stands. We do know that Ben Carson has been surging recently, especially among small donors. This is probably driven by his poll numbers. Jeb Bush, for all of his polling problems, cannot cite cash as a shortcoming. Bush also leads the race for endorsements, which are more than supportive blurbs. To one extent or another, they are promises of shared resources. Ideally, they furnish local aid (think volunteers–someone has to hand out flyers, stuff envelopes, make phone calls, and drive vans around), which is critical in early primary states. When these overlap with strong polling (as they do for Carson at the moment), there is harmony. When they do not, there is discord–as is the case for Bush. At some point, these things must translate into either polling outcomes or votes. If they don’t, and there is no guarantee they will, what once were strengths become weaknesses, signs of unfulfilled potential.

So, what does this mean? This thing is far from over. In fact, it has not really started. Also, a large field signifies nothing all by itself. It is not a sign of inherent division within the party, and it does not necessarily lead to defeat next November. As this excellent piece in Politico points out, large fields are not unheard of in presidential primaries. In 1976, 17 Democrats vied for the nomination. Some were darlings of the Democrat establishment (Birch Bayh and Walter Mondale), and others were harder to categorize (Scoop Jackson, Frank Church). Fringe candidates (Jerry Brown) caught fire, while grenade launchers (George Wallace) threatened to tear the party apart. In the end, an insurgent of a different sort, Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter, who promised to reform Washington and never to tell a lie, won a bitter nomination and the presidency.

The Republicans need to exhale for a bit. Things will change. My hunch is that some the current bottom-tier candidates (Graham, Jindal, Perry, Santorum, Paul, Pataki, Gilmore) will dwindle soon. Expect the race to come into sharper focus around the holidays. Trump will hang in, but other forces will begin to coalesce around a rival–either Rubio or Walker–and then we will reach the end of the beginning.

Bert Wheeler

Bert Wheeler

Jeff Haymond

Jeff Haymond

Marc Clauson

Marc Clauson

Mark Caleb Smith

Mark Caleb Smith

Tom Mach

Tom Mach